Some chapters sample the tropes and tones of their professed genre. Each short chapter examines its content through a lens-or places it in a room-that is summarized by a heading: “ Dream House as Confession,” “ Dream House as Stoner Comedy,” “ Dream House as Word Problem.” The relationship between section and title morphs throughout. The book itself takes a breathtakingly inventive form. Machado’s introductory quotes aren’t just gloss, in other words. (In one passage, she compares her state of mind to that of a gay teen crushing on a same-sex classmate without knowing anything about gayness.) In the book’s opening pages, Machado notes that the word “archive” derives from the ancient Greek word for “house.” She invokes Louise Bourgeois’s theorization of memory as “a form of architecture.” Her intent becomes clear: to imagine an archive, or dream a structure, in which her story can live, surrounded by literary trappings-epigraphs, prologue-that lend it legitimacy. Before she met her ex-girlfriend, Machado hadn’t encountered narratives of queer domestic abuse she lacked context and precedents she could not make sense of her experience. The concept of “archival silence,” Machado writes, captures the idea that certain histories never enter the cultural record. Instead, “In the Dream House” is primarily about the quandary of constructing “In the Dream House.” It is a quandary both because the telling is painful and because Machado, who has no language for this telling, must invent one. Yet the arc of this ordeal, although it forms the book’s skeleton, is not Machado’s true subject. Is it when she flies into a rage after Machado fails to respond immediately to a text? When she digs her fingers into Machado’s arm? Over the course of a formative love affair, the woman-who dwells, witchlike, in a cabin, in Bloomington, Indiana, which Machado calls the “Dream House”-will accuse Machado of cheating throw things at her lie to her manipulate her scream at her and reduce her, again and again, to tears. Just as it is difficult to say when the book begins, it is difficult to say when Machado’s girlfriend, blonde and slight, also a writer, first reveals her nature.

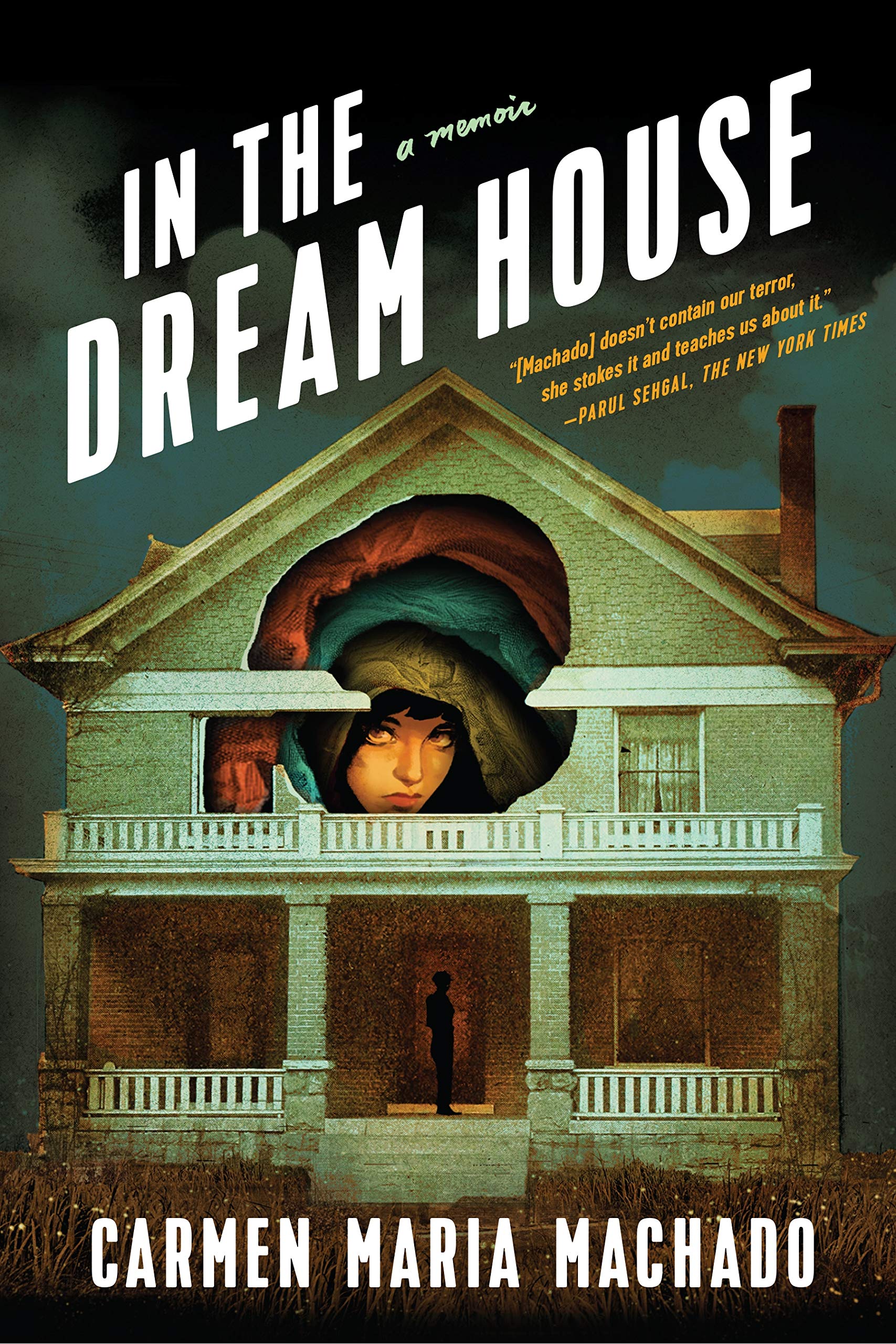

The memoir, by the acclaimed author of the short-story collection “ Her Body and Other Parties”-which was a finalist, in 2017, for the National Book Award-chronicles Machado’s experience in a horrifying relationship. Paging through this front matter feels like waiting for a haunted carnival ride to start, only to be wrong-footed. It contains a dedication, three epigraphs, an overture (declaring the author’s suspicion of paratext), a prologue, and another epigraph. The antechamber of “ In the Dream House,” a new work of memoir-cum-criticism by Carmen Maria Machado, is crowded.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)